Loop - Program Management

Program and project management are important topics which managers are often left to figure them out on their own. This section discusses program management, explaining the desired end state. The next discusses projects, diving deeper into how to achieve this end state.

Tl;dr - How to manage programs?

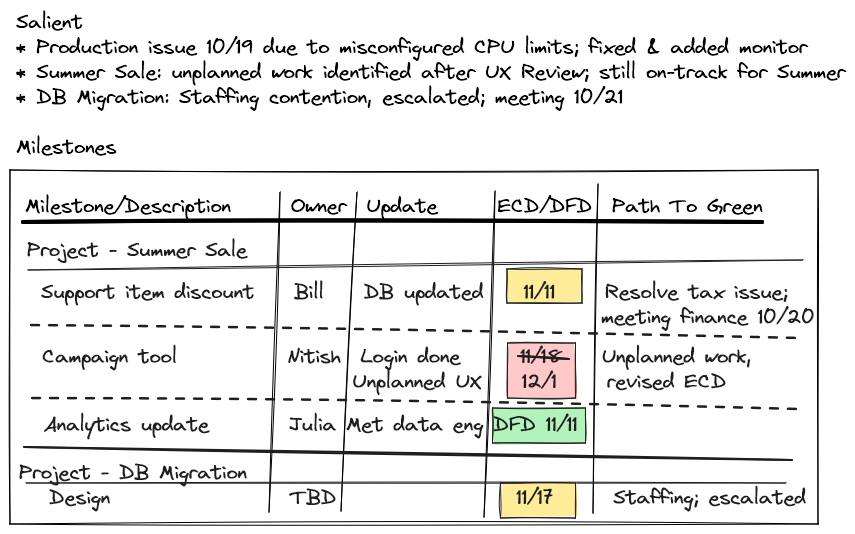

As manager, you maintain a program status for your team and send it to stakeholders every week. It looks like this:

To summarize:

- Salient section

- Milestones table, listing all tracked milestones grouped per project

Maintaining a program status helps provide clear communication to stakeholders but also serves as a forcing function to meet our tenets: expect and foster leadership, work backward and eliminate waste, and create the right feedback mechanisms. However, before we explain how tenets are achieved, let's unpack the process itself.

What's a project?

The projects listed in a program status are loose groupings of related milestones - even if they don't strictly meet the definition of 'project' from a business perspective. It might be 1) a single phase of a larger business initiative; 2) a portion of a multi-org project the team is responsible for; or 3) a collection of tasks, for instance during a bug bash. More on projects in the next section.

What's a program?

A program is a collection of projects. Since software teams rarely work on a single project, teams are generally responsible for a program. One could argue that a program should only be comprised of projects that are related to one another. This distinction is not super useful for our purpose here but, if that's the case, replace 'program status' with 'team status'.

What's a milestone?

A milestone is a significant increment in software functionality that should be widely understandable by non-technical audiences. We'll discuss milestones in more details in the project section.

Who are stakeholders?

Stakeholders are your direct manager, product managers, adjacent software teams and managers, and any other person or group that interacts or depends on the projects your team owns.

How to write an effective program status?

There are two main ideas behind any well-written program status:

- Show, at a glance, week over week changes

- Describe corrective actions, if any

The best program statuses are scanned and promptly discarded. Why? Because they answer all relevant questions without any need for stakeholders to intervene. After a quick read, they're convinced that either 1) everything is fine, or 2) the team has everything under control.

What's the salient section for?

The 'salient' section provides a quick summary of important updates so that readers don't need to read further unless they want more details. This might include new discoveries, completed projects, unexpected delays, production issues, etc. You may prefer a different name, like 'summary' or something similar. Some may also prefer to split this section into 'highlights' and 'lowlights', which is fine.

What's the purpose of each column in the 'milestones' table?

Each column serves a specific purpose, in line with the main ideas discussed above.

- Milestone/Description lists each milestone with a brief description. (The description is not shown above for simplicity.)

- Owner identifies the owner responsible for delivering that milestone, who may or may not be the sole engineer working on it. Note the default owner is always you, as the manager, and this column can be TBD if a specific engineer-owner hasn't yet been identified.

- Update describes related updates since the previous week. It can be empty if there are no updates.

- ECD/DFD is colored with the status of the milestone (see below). It also specifies either 1) the Estimated Completion Date (ECD) or 2) a "Date For Date" (DFD), i.e., the date when an ECD will be available. By default, this column contains ECDs; "DFD" is specified only if the date is a DFD.

- Path to Green (PTG) explains how the team is working on bringing the milestone back on track, and is specified only if the milestone is not green.

What colors to use in the ECD/DFD column?

Milestone statuses are color-coded as follows.

- Green - On track, expected to ship at or before the posted ECD.

- Yellow - At risk, corrective actions required. Yellow is generally a transitive, unstable state between green and red while corrective actions are attempted.

- Red - Off track, not expected to ship on time. If the milestone is on the critical path, the entire project could be delayed.

- Blue - Shipped, no more work required for this milestone. Identifying shipped milestones provides an important, at a glance signal of progress.

- Grey - No longer tracked, the milestone is to be removed. For instance, if a milestone is de-scoped due to business decisions, we want stakeholders to see that delta. The 'update' column should provides details, while the ECD/DFD is colored grey and set to "descoped".

- Blank (no color) - To be determined (TBD). While other statuses should be preferred, it can be useful in interim situations when information is missing. For instance, if priorities shifted just before sending the program status, the state might be unclear. You, as manager, are responsible for clarifying within the week, and possibly sending an interim update.

These status colors are obviously not cast in stone and another scheme might be preferred. Yet, in my experience, they cover all cases that arise in practice and allow consistent reporting week over week.

Why are date for dates (DFDs) needed?

After a milestone is created, its ECD is often unknown. In that case, it could simply remain TBD; why put a DFD? The problem with keeping an ECD unspecified is that it provides no feedback about planning itself. For instance, suppose a milestone needs a written design and a design review: a reasonable DFD could be two weeks from now. Further suppose a week has passed and the design hasn't started: planning is slipping and the milestone is now yellow. Hence, DFDs provide important signals that may require corrective actions. This may prompt reassigning work, shifting priorities, etc.

Estimating when a milestone can be estimated should be trivial and mechanical, say one or two weeks from now. However, this is sometimes infeasible because the work is more involved; for instance, if a prototype is needed, or a multi-step design review involving other teams. In that case, the work required to estimate is itself the milestone. Think about it in terms of indirection: a single level of indirection is fine (DFD), but two levels indicate work needs to be done before estimation can proceed. In that case, the milestone could be "prototype" or "design" and it's that milestone that has a DFD one or two weeks from now.

How to track ECD or DFD changes?

As mentioned above, one of the main ideas is to show week over week differences. This has a few interesting implications for tracking changes to ECDs and DFDs.

- When a DFD is converted to an ECD, the former is shown in strikethrough above the latter and that status remains green. The DFD was met and the new ECD is also green. Blue is not used in this case.

- An upcoming ECD changing from green to red, without transitioning through yellow, is generally a struggling signal - especially for larger milestones. An explanation should be provided as to why the team didn't realize the work was slipping.

- Grey and white milestones shouldn't remain in that state for more than a week.

-

If an ECD or DFD is pushed back:

- The status is automatically red since the committed date was not met.

- The old date is shown in strikethrough above the new date so that readers can see how much the date has slipped.

Note that it might be tempting to set a milestone green that had its ECD reset because the new ECD is on track. However, this would make it harder to scan for delayed milestones and could lull us into complacency. For proof, consider the pathological case of a milestone slipping every week: it stays green forever but never ships. This wouldn't be right.

Why is path to green needed?

The 'path to green' (PTG) column describes corrective actions. Its placement just after the ECD/DFD column is no accident: it allows stakeholders to quickly scan the table to see what milestones are struggling and what's being done about it.

The main question PTGs should answer is "what are the next steps?" because it's the one stakeholders care the most about. For instance, if a milestone is slipping, a PTG could be "Ensure successful deployment Monday". Right, but what if the deployment is unsuccessful? A better PTG could be "Team meeting Tuesday 10/31 to assess Monday release and triage emergent issues". This PTG is necessarily vague - we don't know what/if issues will arise - but still informs stakeholders that any potential delay is proactively being handled. Another PTG example could be "Consider descoping other features". Sure, but what other features, when, and who's involved in that decision? Be precise about next steps, even if you don't know exactly how the situation will unfold. As managers, we don't make all the decisions and don't know the future, but - as the name implies - we manage.

Note that in most cases, PTGs don't need to be heroic. If an interim milestone is slipping by one week, without any further impact, the PTG could simply be "Revised ECD, no downstream impacts". The red status served its purpose: it signaled a slip, we assessed the impact, and, since there was none, we moved on.

How to prepare a program status for review?

Every week, 1) a copy is made of the previous status, 2) strikethrough dates are removed, and 3) red milestones that had ECD resets are flipped back to green. The status is ready for team review once again.

Some could be tempted to leave previously committed (strikethrough) dates to keep a historical record, but this is unadvisable. For once, it makes the text cumbersome to read, with milestones taking too much vertical space. More importantly, previous dates don't convey why they were changed, which might be due to any number of reasons: product de-prioritization, business decisions, staffing, etc. In essence, keeping previous ECDs communicates "misses" without communicating any rationale for these misses. Hence, stakeholders could get a false impression the team is not delivering, which could in turn reduce team engagement and morale.

Not to belabor the point, but making a weekly copy instead of replacing in place is strongly suggested. It's highly likely you'll want to refresh your memory about past events at some point.

How to order milestones?

Milestones are ordered by the latest ECD/DFD date, regardless of whether the date is an ECD or DFD. TBDs are put at the end. This scheme is, once again, to ensure stakeholders can absorb the information quickly: readers shouldn't have to do any mental gymnastics to understand the order in which milestones will be delivered.

How does program management expect leadership?

Managing team commitments via explicit milestones is directly aligned with all three leadership principles.

-

Ownership: Engineers own specific milestones, which sets clear expectations about what needs to be delivered and when. As we'll see later, these commitments are not parachuted from the top but made by engineers themselves, who own the entirety of their work end-to-end - starting from requirements, to design, to estimation, to delivery. Owning the solution, setting goals, rallying as a team, working with clear focus, hitting consecutive milestones – these are empowering, energizing, and deeply satisfying on a personal level. Doing so demonstrates ownership and leadership.

-

Deliver Results: As mentioned before, the right results are not great functions, clever software designs, or an elegant architecture. Rather, they further customer-focused goals, being delivered at the right level of quality and in a timely fashion. In other words, a large part of delivering results is delivering milestones. It's not about moving cards on a board and losing track of the cathedral we're building, but keeping the cathedral center stage and delivering what matters to customers. Program management provides complete transparency about what results are being delivered, by whom, and when.

-

Debate Openly, Commit Fully: Making milestones explicit ensures engineers can review and discuss the desired and current state of projects, which is an important part of debating openly. Notably, they're expected to recover or escalate if a milestone is struggling, or if unplanned work is discovered. Conversely, should a decision be made that they disagree with, milestones track the team's commitment to the chosen result. For instance, built-in expectations around target dates ensure there's a healthy tension between making the right engineering decisions and overall cost.

Like any other professional endeavor, software engineers should be expected to deliver on high-value milestones, not individual tasks, and fully own the execution of this work with minimal interference. This ensures no micromanagement or other aberrant management behavior.

How does program management foster leadership?

Since program management expects leadership, it's also an incredibly powerful vehicle to foster leadership. For instance, a new team member first exposed to the question "Are you still confident this milestone will ship on time?" immediately realizes the leadership expected of them. Likewise for many other program management questions. A hypothetical discussion could go like this:

- How did the milestone progress this week, are you still confident it will ship on time?

- Given it's at risk, what are we doing about it?

- Supposing it slips, how would it impact other milestones you own?

- This milestone was red last week, why is it still red this week after we reset the ECD?

To be clear, these questions are genuine collaborative inquiries - psychological safety is paramount. Still, there's no possibility of losing track amidst busy work and moving cards on the board: we're talking in plain language about delivering meaningful results.

Simply put, program management is a process that grows leaders - it's almost magical.

How does program management enable working backward?

Working backward is at the core of program management. We first determine what needs to be delivered, how, and when; and then track how we're doing against that commitment. By defining the desired end state and committed time frame, we're not just working forward with no clear target in sight. We regularly review the target and inevitably work backward from it.

How does program management eliminate waste?

As mentioned before, waste comes in many form, and program management eliminates a lot of it. For instance:

- Adding unnecessary functionality is a well-known issue (YAGNI), though there are often no clear mechanisms to prevent it1. Program management essentially solves this through ongoing ECD reviews: there's an inherent tension to meet timelines, which reins in unnecessary work.

- Not planning for upcoming functionality (the exact opposite of the above) is even costlier due to expensive rework. While we can't guarantee rework will never happen, we can at least let engineers consider larger chunks of functionality through narrative requirements, let them craft solutions that are more flexible for the same cost, and draw on the team's collective knowledge - aka, designing. In other words, program management allows engineers to determine the how: what's the best overall approach and project shape.

- Delaying business value is due in part to not prioritizing the right projects and milestones. Program management addresses this via regular, high-level review of the entire slate, including other projects and initiatives.

How does program management create the right feedback mechanisms?

Weekly program reviews are akin to regular health checks and inherently generate feedback. Is it the right feedback though? Well, it 1) detects deviations and issues early on, before they become serious; 2) acts as a forcing function to address every week; 3) ensures cross-functional (re)alignment, usually before plans become too rigid; 4) protects teams from over commitment and work-life imbalances; and 5) provides significant opportunities for leadership and career development. Hence, yes, program management creates the right kind of feedback.

Is it important to actually send the program status?

To send a program status, it must exist in the first place. Not sending it is a good way to ensure it falls in the cracks. Also, why not use this opportunity to inform stakeholders?

Is program management really needed?

It's tempting to think the benefits of rigorous program management can be obtained without doing the above. If you find a way, let me know, because I haven't found one.

That said, the format can be changed. Although I have found simple text documents to work well, I had one manager who got pretty far recreating the format using a well-known software management tool. Epics were colored, custom fields were added, and a view was created that was close to the one above. Ultimately, the format doesn't matter, as long as we have the same team conversations and meet the same tenets.

Is program management the responsibility of software managers?

Yes, if only because it's an important career and leadership development tool.

However, some projects may be managed by a (Technical) Program/Project Manager. Great! In that case, no need to duplicate work as long as you get the same signals and team conversations. As always, let people take stuff off your plate, more time for you to focus elsewhere.

How to handle small ad hoc or engineering-related tasks?

Ad hoc work is typically not surfaced in program statuses, assuming it represents a relatively small fraction of the team's time. However, exceptions include important updates like production outages, work that impacts current initiatives, or special events like bug bashes. That said, if the team regularly spends significant time on ad hoc work, it might be helpful to provide visibility via an emergent or engineering "project", with tasks listed as milestones.

As always, use your best judgment because tracking small tasks in program statuses is cumbersome and in direct tension with eliminating waste.

Help! What to do if my milestones are all yellow and red?

If your program status doesn't look like a Christmas tree from time to time, you're doing it wrong. We'll discuss how to handle struggling milestones in the project section.

-

Anecdotally, I've seen some flavors of Agile deal with YAGNI by insisting software should never be designed. I'd charitably describe this as throwing the baby out with the bath water. As we'll see later, software designs are a critical piece of any well-functioning team, one of the most important feedback mechanisms, and one of the best ways for engineers to mentor one another. ↩