Execution

Tl;dr - How to set up execution?

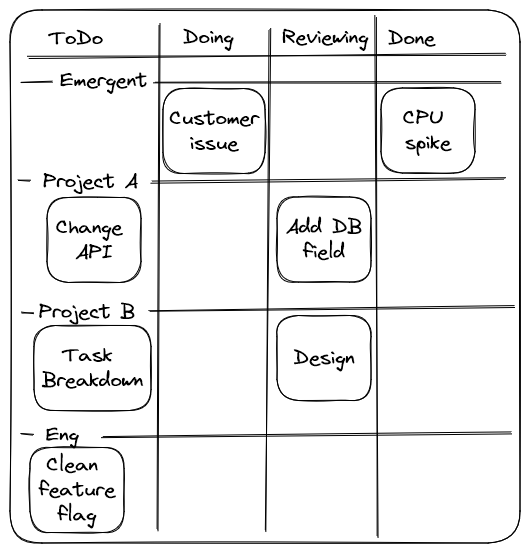

Here is an example of how to set up a well-crafted Kanban execution process. Specific names and labels can obviously be changed based on team preference.

- Use a Kanban board with swimlanes

-

Each task on the board:

- Represents actual engineering work, not requirements or features

- Is assigned to a single engineer-owner (not represented here for simplicity)

- Takes ~0-5 days to complete by its owner

-

Swimlanes, in order of priority from top to bottom:

- Emergent for production issues, or quick time-sensitive product/business requests.

- One lane for each Project, in priority order. This list should be short.

- Eng for engineering work not related to a project: refactor, cleanup, etc.

-

Columns (e.g., task state):

- Backlog - not represented here, ideally your backlog lives in a different view

- To Do

- Doing

- Reviewing

- Done - these are removed from the board after some time

- Cancelled / Archived - not shown here; shouldn't live on the board for long, if at all

- (One or two additional states are ok, depending on context)

-

WIP limits are optional, as long as tasks are flowing

This is basic functionality any Kanban software provides, no need for anything fancier - serious. As we'll explore below, this simple process gives engineers significant latitude in how they work, requires minimal coordination and manual maintenance, and provides good feedback signals. Hence, this setup aligns with our tenets: 1) expect leadership, 2) work backward & eliminate waste, and 3) create the right feedback mechanisms.

What is "execution"?

Execution is essentially a team's to-do list, and the process for completing this work. It involves tracking, organizing, communicating, and completing the work that needs doing: what tasks have been discovered, who they're assigned to, and what state they're in. No matter how a piece of work came into existence or became a team's responsibility, execution is the last stage before it ships.

In most software teams, execution is managed via Kanban, Scrum, Scrum-but, or some homebrew mechanism like OKRs and individual to-do lists. In my experience, Kanban is the better option. It's simple, doesn't get in the way, and doesn't require unnecessary work - which would be wasteful. It also lends itself well to management by exception, which is important to eliminate waste.

Who owns execution?

As manager, you own execution for your teams. That said, a good captain trust their crew. You'll lean on your team's insight to fine-tune and craft a process that works for them. Hence, day-to-day execution is largely managed by the team, and you role is to keep a watchful eye, providing a gentle nudge to steer back on course when needed.

For this to work smoothly, we'll need a process that lends itself to management by exception. That is, most day-to-day events should have clear outcomes that can be self-managed and don't need escalation to you or tech leads. Only situations deviating from the norm should be treated exceptionally. This approach not only empowers the team but also ensures that your involvement actually adds value.

What is WIP and why is it important?

Think of WIP (Work In Progress) as a juggling act, where each ball is a task that was started but isn't finished yet. The more balls you're juggling, the harder it is to keep them all in the air. Juggling with 100 balls, or with bowling balls, is nonsensical - WIP matters.

Tasks should be small and flow unimpeded; any task not flowing directly contributes to waste. In Kanban, a lack of flow can be seen by accumulation in certain columns. This waste can take many form, for example:

- Working on too many concurrent initiatives results in unnecessary context switches, loss of context, and sap motivation, delaying a project's business value;

- Large/complex code reviews, unresolved design issues, or dependency chains lead to stalled tasks, rubber stamping, loss of momentum;

- Infrequent releases or frequent rollbacks require extra work and coordination to unwind;

- Etc.

Reducing WIP reduces waste, and as manager it's one of the main thing you'll pay attention to.

How to split work into tasks?

Breaking down work into granular tasks is like building a mosaic — each small piece contributes to a larger picture. Tasks are the individual, manageable units of work that, when combined, create the functionalities and features of your software.

- Focus - A task is engineering work, like adding a table to a database, or incorporating a new parameter into an API.

- Size - Aim for tasks that can be comfortably completed by an individual in a few days. This keeps work manageable and ensures a steady flow.

- Creation - Tasks can spring up from anywhere, be it related to a project, a bug fix, or a production issue. Any engineer can identify and create new tasks, based on discoveries in a collaborative environment.

- Priority - Task priorities can shift at any time, mirroring the fluid nature of software development. Tasks might move to the backlog, be readied for action, or pushed to the top of the to-do list depending on their urgency and relevance.

By design, tasks don't need to:

- Represent complete customer-facing features.

- Meet some specific description format or template.

- Be estimated or reviewed by the team.

- Be planned for.

Should there be multiple types of tasks?

Some teams prefer to have multiple task type: bugs, spikes, tasks, sub-tasks. That's fine, go with whatever the team prefers.

Why should tasks be engineering-focused?

aka: Why not track user stories or epics?

Epics and User Stories can be tracked, but these are requirements that outline customer and business narratives - the 'what' and the 'why'. They describe what feature we're adding and why we're adding it, but not engineering work - the 'how'. To reuse our mosaic example, the big picture is the epic, while the process of cutting, painting, and placing individual tiles are the tasks.

This distinction is crucial:

- Features need multiple engineering tasks to be implemented - a mosaic is not composed of a single piece.

- Multiple tasks can be worked on in parallel to reduce WIP - different section of the mosaic can be worked on simultaneously.

- Tasks are sometimes reassigned based on unplanned conditions to reduce WIP - tiles might need to be reassigned if a section turns out to be more difficult.

- New tasks are routinely discovered during development that need to be tracked and assigned - the initial tiles cut or color might not fit the vision exactly.

By focusing on engineering tasks as the primary unit of work, you ensure that the actual 'doing' part of software development is efficiently managed and tracked. If epics or user stories were used as the most granular work items, it would be like trying to create a mosaic without focusing on individual tiles. Engineers would need a separate system to track their detailed work, leading to redundancy and potential loss of critical information on work progress. This approach would not eliminate waste and not create the right feedback mechanism - not meeting two of our tenets.

Can stories be written as tasks?

Can architects design buildings by focusing on individual bricks? While possible, perhaps, it's not practical or effective.

Requirement writers, like architects, may not possess the technical know-how to break down features into actionable tasks. They can outline the broad strokes of a feature (blueprint), but the detailed construction plan (tasks) is best left to engineers. Requirements are better crafted as high-level narratives, which allows the team to review and understand the overall vision before diving into the specifics. Engineers then take this vision and decide the best way to implement it, breaking it down into manageable tasks.

More importantly, working backward means starting with the end in mind (blueprint) to determine the steps to get there. If engineers are only given small, predefined tasks, it's like showing a construction team only a tiny section of the blueprint at a time. By presenting them with the full design (the overarching business goals and customer perspectives), engineers can devise a variety of solutions, each with its own trade-offs. These solutions can then be reviewed and refined based on business value and constraints.

Can stories be written to be doable in 2-week sprints?

Can every phase of a construction project involve exactly 50 bricks? While it's an intriguing idea, it's again not very practical or effective.

Just as architects design buildings based on need and purpose rather than a predefined brick count, requirements should be defined by their objectives and not just to fit a time box. If a project naturally aligns with a smaller scope (like a 40-brick building), that's great. But most projects are more complex, and we shouldn't treat exceptions (small scope) as the norm.

That said, regardless of scope, a building can be constructed in phases, each delivering incremental value. The basement first, to protect from tornados, then the kitchen for practicality, then bedrooms for comfort. That's really what we're after, right? Let requirements (blueprint) provides a comprehensive view of the desired outcome, and project plans determine how to approach the building phase by phase. More on project planning in future sections.

How are tasks obtained from requirements?

Translating requirements to engineering tasks involves translating the 'what' and 'why' into the 'how' of actionable tasks. This process is engineering work in itself, and tracked with... tasks!

This process typically involves: 1) requirements review, 2) software design, 3) work breakdown, 4) project planning, and 5) execution itself, including iterative task refinements. Detailing each step is outside our scope here, but it's important to note that they happen for every single feature, either implicitly or explicitly. When the scope is small, implicit is the way to go to move faster. However, there's a point where explicit becomes beneficial to the whole. More on this when we discuss project planning.

Why can tasks be created at any time?

Tasks will come from different sources and contexts. For instance, an engineer could create a task for another team member after an impromptu discussion, or after seeing a problem on a Production monitor. New tasks are also often discovered during development. This is the norm, not an exception, and our execution process must handle this situation as a matter of course.

Why should tasks be doable by individuals?

Tasks should be owned and doable by individuals to reduce unnecessary communication, coordination and, ultimately, WIP. This may involve others, for instance design or code reviews, but one engineer remains the single owner, who does most of the work and completes it within a few days. To use our previous mosaic example, a single engineer should own the tangible result of placing that specific tile at the right place.

To be clear, this isn't to say there's no place for collaborative work - exceptions should be made as needed. However, co-owners are generally the exception, not the norm, and the Ownership leadership principle should steer us in the direction of having explicit owners.

Why can tasks be re-prioritized at any time?

New tasks are often discovered during development that have higher priority than previous ones. Examples include production issues, emergent business priorities, or unplanned work related to current projects. Tasks can also be split or reassigned to other team members on short notice to reduce WIP. This is the norm, not an exception - and it's entirely the prerogative of engineers to determine task priorities.

That said, teams are expected to focus on prioritized initiatives, not on something completely different - which mechanically means working on Kanban tasks from top to bottom. For instance, if the team is struggling to meet an upcoming deadline, fixing a Production issue might take precedence, but not embarking on a re-architecture. This may seem obvious, but monitoring the board is part of creating the right feedback mechanisms and may signal to the attentive manager that a gentle intervention is required.

Why use swimlanes?

While swimlanes are not strictly required, their layout in order of priority helps visualize, prioritize, and self-assign tasks. For instance, a project close to completion can be monitored at a glance by looking at its associated lane; or a Production issue can be prioritized by putting in the 'emergent' lane. Of course, emergent priorities need to be separately communicated to the team to find an owner - not everyone will be monitoring the board at all times.

Why are tasks not estimated, yet take 'a few days'?

It might seem paradoxical to not estimate tasks, yet talk about them taking 'a few days'. This is because these are really two different approaches to estimation. A 'few days' is an informal, broad-brush prediction based on an engineer's initial assessment of the work. This forecast comes with a wide margin of error – it's more about setting a general expectation than pinpointing a precise completion date.

Obviously, the number of tasks offers a glimpse into the workload, but it's not a rigid schedule. It's a way to gauge the work ahead, not a commitment to specific completion dates or a guarantee against new priorities emerging.

How to plan projects without estimation?

Estimation should still happen, but only if required and not at the task level. More on project management in future sections.

Why should tasks take a few days?

Setting a general timeframe of a few days is not an ironclad rule, but a practical guideline with several advantages:

- Shorter tasks means better flow and less WIP. It increases the odds that work started will also be completed, reducing waste.

- It allows emergent work to be handled rapidly without interrupting WIP.

- It ensures work is regularly reviewed by the team, either through code review, design review, etc. This result in better team engagement and less rework - effectively reducing waste.

- It helps people dependent on the work to determine when they will be unblocked.

- It provides coarse feedback on the amount of work remaining.

That said, it's the norm to realize tasks will take longer than anticipated, not an exception. In that case, the task should simply be split. Engineers are empowered to create and reassign tasks without interference or ceremony.

How to determine project completion dates from the board?

Just as observing the daily work at a construction site doesn't reveal the exact date the building will be completed, the Kanban board doesn't directly indicate when the project will reach completion. The board serves as a tool for engineers and is tailored to the details of tasks at hand, not for providing a bird's-eye view of the project's end date or aligning with broader business objectives.

Many proposed frameworks either conflate execution state with project state, or purport to derive one from the other automatically. Both are destined to fail. While execution state does provide input signals into project state, they need to be correctly interpreted AND weighed against expecting leadership. Shipping projects on time is not mechanical or based on a formula, and we'll dive deeper in future sections.

When should tasks be assigned to specific engineers?

Teams self-manage assignment of tasks based on availability, preference, career objectives, and other factors. Hence, tasks are moved to a ready state unassigned, so engineers assign work themselves. That's the norm.

That said, there are cases when tasks can be directly assigned to a specific engineer. For instance, assigning a critical Production issue to the domain expert, or a design for career growth. As manager, you can gently sway things one way or another, though assigning tasks should be the exception.

What feedback signals to look for during execution?

There's no magic when it comes to monitoring execution. As manager, you've been in the trenches and should have a good sense for what to monitor. Here are a few signals:

- WIP limits & task flow. If tasks start piling up in a column, it’s like widgets piling up on a conveyor belt. This could stem from various issues like ineffective tools, slow processes, or dependency problems.

- Task granularity. If tasks are too big, the work might not be broken down effectively, or multiple unrelated tasks could be lumped together, making it difficult to track and manage progress.

- Tasks reverting to previous states. Tasks reverting to previous stares (e.g., from 'reviewing' to 'doing') is akin to a product failing quality checks and being sent back for rework. It indicates an underlying issues such as inadequate testing or ineffective design reviews. Related to this, tasks state should accurately reflect reality - something to monitor as well.

- High rate of task creation. Once the initial cone of uncertainty is past, task creation should decrease and become predictable. A lot of new tasks created for a project whose ship date is approaching is often a struggling signal. Related to this, as good leaders, engineers should explicitly state that a project is struggling; if they don't, it can be a signal that psychological safety is lacking.

- Lots of ad hoc tasks. Firefighting can easily lead to loss of morale or missed commitments, this is something to monitor closely.

- Underestimating "trivial" tasks. Engineers may sometimes downplay the complexity of remaining tasks, either due to optimism or lack of psychological safety. As manager, it's important to approach these situations with a cool head and a healthy level of skepticism to ensure your team doesn't overcommit.

Are recurring team meetings required to drive execution?

Most execution-related discussions should be driven by engineers themselves - without any need to micromanage these interactions. For instance, if an engineer needs to discuss specific details on how to implement an interface with another engineer, they can do so 1-on-1. Likewise, engineers should directly communicate with Product Manager, UX Designer, or adjacent teams to discuss specifics. There is rarely a need to involve the whole team in these detailed matters, and curtailing reduces waste.

That said, whole-team touch points add value. We'll discuss this topic more in a future section, but to provide a quick glimpse: regularly meet as a team (say, 3 times a week), but also follow team preferences if they want to meet more often.

Is it ok to freeze commitments for two weeks?

aka: Why not use 2-week sprints?

Emergent work can arise due to production issues, new business requirements, newly discovered work related to current projects, or any number of normal situation. Blocking progress on this type of work for days or weeks is generally not acceptable. Of course, most scrum-type approaches will leave an allowance for unplanned work, or allow modifying the current sprint. However, emergent work is most likely the norm, not the exception, so why not adopt a process that better fits this reality?

The crux of the matter is that there is really no need to plan time boxes in the first place. Estimating stories, determining what tasks the team can commit to, aligning work to a sprint, managing a burn down chart - and doing it again when the inevitable emergent issue arises - all this work doesn't contribute to the bottom line. Teams should have wide discretion in how they manage execution, without any micromanagement of tasks on the board.

To be clear, the underlying rationale for many scrum ceremonies is understandable. For instance, refinements expose the team to upcoming requirements, and velocity helps determine when features will ship. However, these mechanisms are inherently wasteful, don't have the right feedback mechanisms, and don't include leadership as a core component - i.e., they don't meet our tenets.

Are there exceptions to these rules?

There are always exceptions. A task can take two weeks and that's ok, because we don't need to split further or parallelize. A task can remain stalled in a column for 3 weeks and that's ok, because we're waiting for someone on vacation. Don't do work that doesn't need doing.

Scrum is mandatory, what should I do?

In situations where Scrum is non-negotiable, and in the spirit of choosing one's battles, we can make the process more efficient with little fanfare. Given that 1) burn down charts rarely have any material impact, 2) unplanned work is inevitably added to in-flight sprints, and 3) sprints are often not completed, we can mentally model the work as a continuous stream, exactly like Kanban, and pay no heed to unnecessary artifacts. Hence, consider the following strategies to eliminate waste and empower the team to focus on more meaningful work:

- Simplify bug estimation: Assign a standard value to all bugs (e.g., 2 points), ideally based on historical data. This avoids time-consuming discussions during refinement meetings and acknowledges the inherent difficulty in estimating bugs.

- Ask for narrative requirements: Most Product Managers are happy to write narrative-based requirements as a single "one-shot" - it's generally less work for them! As required, these narratives can be written directly in the tool as epics or stories, with minimal loss of efficiency.

- Use spikes: If a Story cannot be estimated, convert it to a Spike. This is typical for Scrum implementations and shouldn't be a change to the process. Assign spikes a predetermined number of points (e.g., 3 points), assuming it will require a written design and review. Once the design is reviewed, breakdown the work into engineering tasks.

- Streamline estimation: Based on the requirement narrative and design-driven tasks, have an engineer estimate the work before refinement meetings. During the meeting, only discuss estimates if at least one engineer believes it should be increased by more than one increment. For instance, if using fibonacci, discuss a 3-point story only if someone thinks its 8 point or more. (Conversely, no need to discuss if an engineer believes it's 1 point, because the highest estimate should be taken.)

- Task assignments: Assign stories to a feature owner (possibly tech lead), but create tasks or sub-tasks for the actual engineering work. Assign these to the actual engineer-owners. (Most scrum boards have this functionality.)

- Incomplete tasks: When the sprint ends, mechanically carry over remaining tasks to the new sprint, without further discussions. Also consider skipping sprint planning altogether, if possible, by filling the new sprint with tasks in ready state, or by asking engineers to assign 3-4 tasks to themselves.

Implementing these heuristics can help navigate the Scrum process in a rigid corporate setting without causing disruption. Propose each change as an experiment, framing it as a practical solution to improve efficiency. For example, standardizing bug points can be justified as a way to reduce time spent on difficult estimations, with minimal impact on overall velocity. This approach allows for incremental improvements within the existing framework, making the process more manageable and less time-consuming.